Bloomsday 2025: Celebrating Ulysses by James Joyce

A selection of material exploring the world of James Joyce’s Ulysses is now on display on the first floor of the McClay Library. Set over the course of a single day – 16 June 1904 – the novel follows three Dubliners: Leopold Bloom, Molly Bloom and Stephen Dedalus. Blending stream-of-consciousness narration, satire, and linguistic experimentation, Ulysses echoes elements of Homer’s Odyssey, reimagining myth within the context of everyday life in Dublin. The day it depicts, now known as Bloomsday, is celebrated by readers around the world each year.

The First Edition and the Women behind Ulysses’ Publication

“Our national epic has yet to be written”

– Ulysses Episode. 9, Scylla and Charybdis

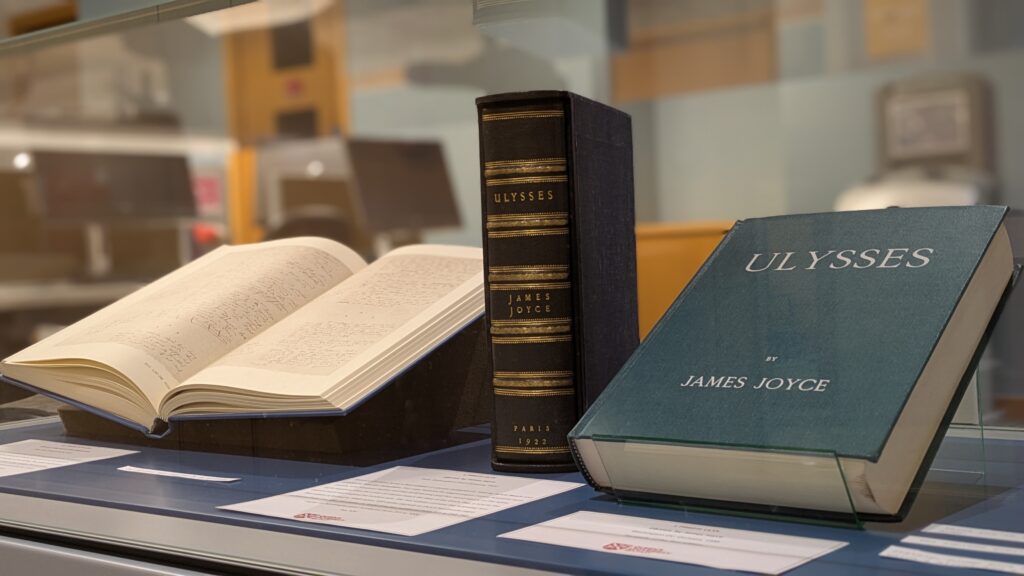

Written over a seven-year period, Ulysses was first published by Sylvia Beach in 1922. Special Collections holds a first edition of the novel, number 526 of 1,000 copies. It features its original paper covers, bound in hard boards, with full green leather binding, gold tooling and five raised bands on the spine. Joyce requested that the cover of Ulysses match the blue of the Greek flag, a nod to the classical myth that inspired his modern epic.

Joyce’s masterpiece may not have reached readers without the efforts of several radical women who defied the stringent censorship laws of their time and championed literary modernism. In 1918, Margaret Caroline Anderson and Jane Heap first published episodes of the novel in serial form in their avant-garde American literary magazine, The Little Review. Their work was cut short when they were prosecuted in the Ulysses obscenity trial in 1921. In 1922, Sylvia Beach – the American-born founder of the English-language bookshop Shakespeare and Company in Paris – offered to publish Ulysses following discussions with Joyce about his difficulties securing a publisher. Alongside Harriet Shaw Weaver, whose patronage made the writing of Ulysses possible, these women’s commitment to modernist literature and refusal to conform to moral and cultural restrictions was vital in securing Ulysses its place in history.

Painting Joyce

“The supreme question about a work of art is out of how deep a life does it spring.”

– Ulysses Episode 9. Scylla and Charybdis

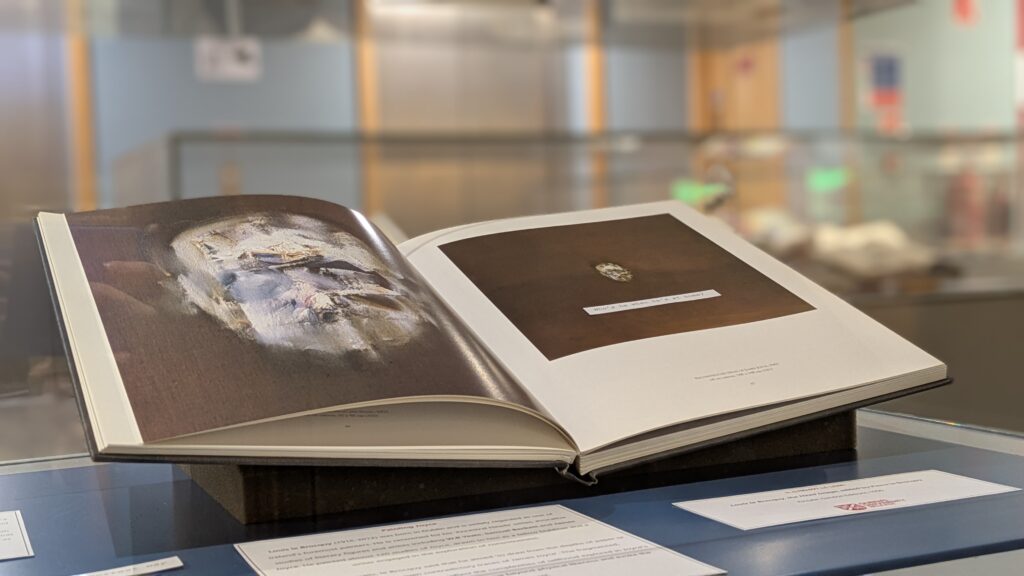

Louis le Brocquy (1916-2012), one of Ireland’s most celebrated painters, was drawn to Joyce both as a fellow Dubliner and a radical explorer of consciousness. Le Brocquy created nearly 120 studies of Joyce, aiming, in his words, “to draw from the depths of paper or canvas changing and even contradictory traces of James Joyce.” These fragmented portraits mirror the complexities of selfhood explored in Ulysses, moving beyond physical likeness to evoke the writer’s interior world.

Dear Dirty Dublin

“As he set foot on O’Connell bridge a puffball of smoke plumed up from the parapet.”

– Ulysses Episode 8. Lestrygonians

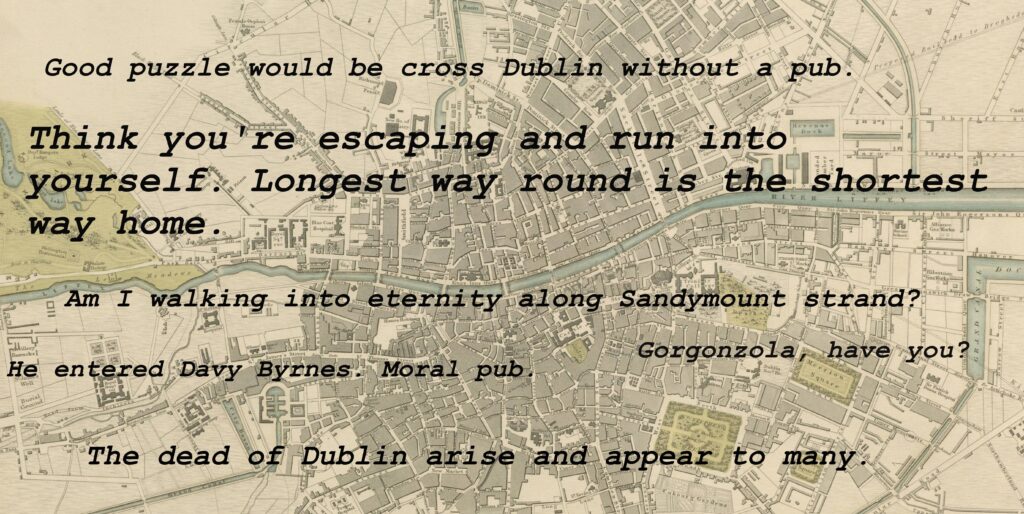

Though written in Trieste, Zurich and Paris, Ulysses is firmly rooted in Dublin. The city rings out from the novel – its streets, smells, voices and rhythms vividly brought to life. From Leopold Bloom’s lunchtime gorgonzola sandwich and glass of burgundy in Davy Byrne’s pub, to Paddy Dignam’s funeral procession from Sandymount to Glasnevin Cemetery, Joyce offers readers a rich sense of life in Dublin in the early 20th Century. He achieves this not by laying out the city in tidy detail, but by capturing its pulse through the lives of its inhabitants. He once famously declared that if Dublin “suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed out of my book.”

The Music of Joyce

“He crossed under Tommy Moore’s roguish finger. They did right to put him up over a urinal: meeting of the waters.”

– Ulysses, Episode 8. Lestrygonians

A tenor with a lifelong passion for music, Joyce competed in the 1904 Feis Ceoil and once shared the stage with the celebrated tenor John McCormack. Ulysses – particularly the “Sirens” episode which Joyce claimed to have structured as a musical fugue – draws deeply on musical and sonic techniques. For Joyce, language was something to be heard as much as read and he invited readers to sound his writing aloud to reach deeper understanding.

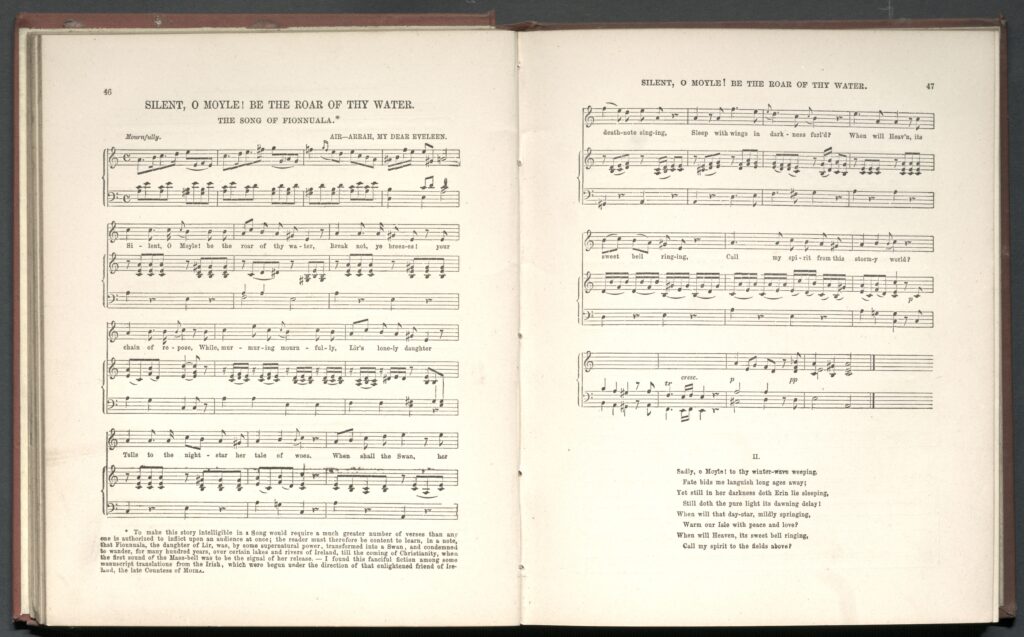

Thomas Moore’s “Silent, O Moyle” (also known as “The Song of Fionnuala”) is referenced in Ulysses, Finnegans Wake, and the short story “Two Gallants.” As the author of Irish Melodies, Moore was widely regarded in the 19th Century as Ireland’s national bard. In Joyce’s work, “Tommy” Moore is both evoked and critiqued. Where Moore’s songs were often associated with a sentimental nationalism, Joyce sought to challenge traditional forms and reframe Irish identity. From “The Lass of Aughrim” in “The Dead”, which stirs memories in Gretta Conroy, to the recurring references to “Love’s Old Sweet Song” in Ulysses, a piece Molly Bloom is set to perform on her concert tour, music and sonic texture are woven into Joyce’s narrative structures, characterisation and linguistic sensibilities.

Molly Bloom’s Soliloquy

“…I was a Flower of the mountain yes when I put the rose in my hair like the Andalusian girls used or shall I wear a red yes and how he kissed me under the Moorish wall and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.“

– Ulysses, Episode 18. Penelope

The final, and arguably most famous, lines of Ulysses come from Molly Bloom’s soliloquy in the “Penelope” episode. Written in an unpunctuated, stream-of consciousness style, Molly’s voice captures the wild intimacy of interiority and memory as she lies in bed beside her sleeping husband, Leopold Bloom. Molly serves as a counterpart to Penelope in Homer’s Odyssey, and is based in part on Nora Barnacle, Joyce’s then partner and later wife. The couple’s first date took place on 16 June 1904, the day on which the novel is set.

Ghosts of Joyce: Influence and Echoes

“What is a ghost? Stephen said with tingling energy. One who has faded into impalpability through death, through absence, through change of manners.”

– Ulysses, Episode 9. Scylla and Charybdis

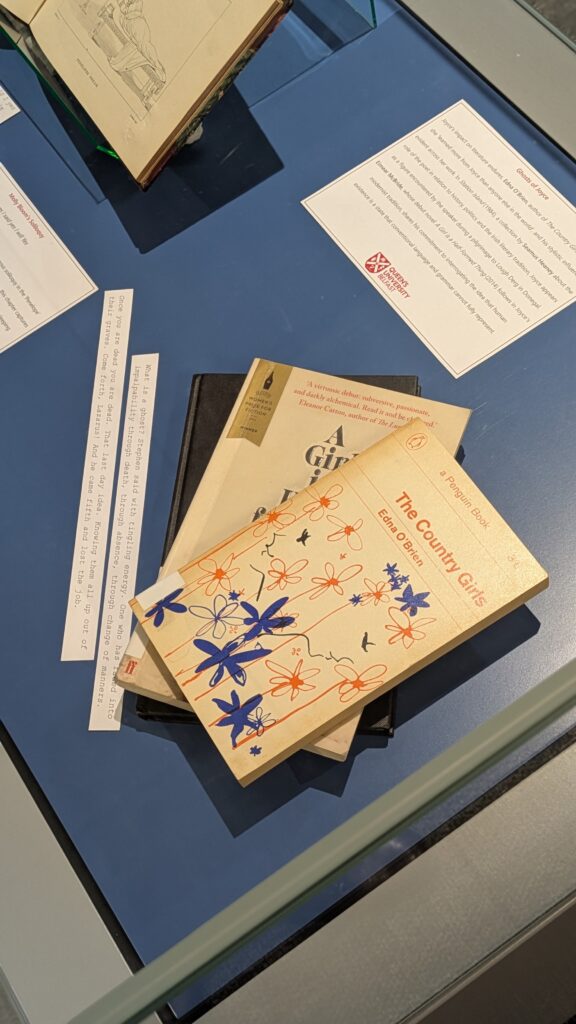

Joyce’s impact on literature endures. Edna O’Brien, author of The Country Girls (1960) said she “learned more from Joyce than anyone else in the world”, and his stylistic influence is evident across her work. In Station Island (1984), Seamus Heaney‘s meditation on the role of the poet in history, politics and the Irish literary tradition, Joyce appears as a guiding figure encountered by the speaker during a pilgrimage to Lough Derg, Donegal. Eimear McBride, whose debut novel A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing (2014) extends the innovations of modernist writing, shares Joyce’s commitment to interrogating the limits of conventional language and grammar as tools for representing human consciousness. While such approaches may render the reading experience demanding, they reflect the complexity of lived experience – something that, despite Molly Bloom’s frustrated plea in Ulysses, cannot always be told in “plain words”.

For those interested in exploring the world of Joyce and Ulysses through materials held in Special Collections, the items listed above – and many others – are available for consultation in the Special Collections Reading Room. Additional highlights include:

- Ulysses by James Joyce, First Edition Facsimile

- Ulysses: A Facsimile of the Manuscript

- The Klaxon, Winter 1923-24: Literary magazine responsible for publishing the first positive review of Ulysses in the Irish Free State.

- Dana: An Irish Magazine of Independent Thought, No. 4: Literary magazine which published Joyce’s short poem “Song” in August 1904, when he was just twenty-two.

- Supplemento Estetico Ai Manuali Tipografici I, II, III, IV: Supplement dedicated to the history of 20th-century fine printing, including a section on Maurice Darantiere’s printing of Ulysses in Dijon.

- “Your friend if ever you had one”: The Letters of Sylvia Beach to James Joyce

- The Little Review “Ulysses”

- The Book about Everything: Eighteen Artists, Writers and Thinkers on James Joyce’s Ulysses

Blog post written by Laura Sheary, Library Assistant, Special Collections & Archives.